Development Aid with Chinese Characteristics?

China is rapidly emerging as one of the biggest actors in the developing world. Is this a new, benign, and better actor? Or is China luring countries into serving its expansionist geo-politics?

The all-encompassing "belt and road" design

In the last fifteen years, the world has seen China’s impressive rise as a major player in the international development finance. In such a short period, China has transformed from being an aid recipient to a net aid donor, rivaling traditional major donors and lenders. It has also financed big ticket infrastructure projects in mostly low-income countries.

A number of factors are driving China’s profile rise in global development finance. Despite its growing economic influence, its role in major international financial institutions such as the US-led World Bank and Japan-led Asian Development Bank (ADB) remains limited. In response, it has promoted the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Silk Road Fund with a view to bridge the huge financing gap in infrastructure investment demand and supply in Asia-Pacific. The ADB and World Bank not only failed to meet the demand for infrastructure investment in developing countries but also came with tighter conditions such as market-oriented reforms. China has taken advantage of this not only to edge out Japan and US in the region, but also to enable it to offload some of its excess industrial capacity, secure markets and raw materials to support export activity, and arrest China’s economic slowdown.

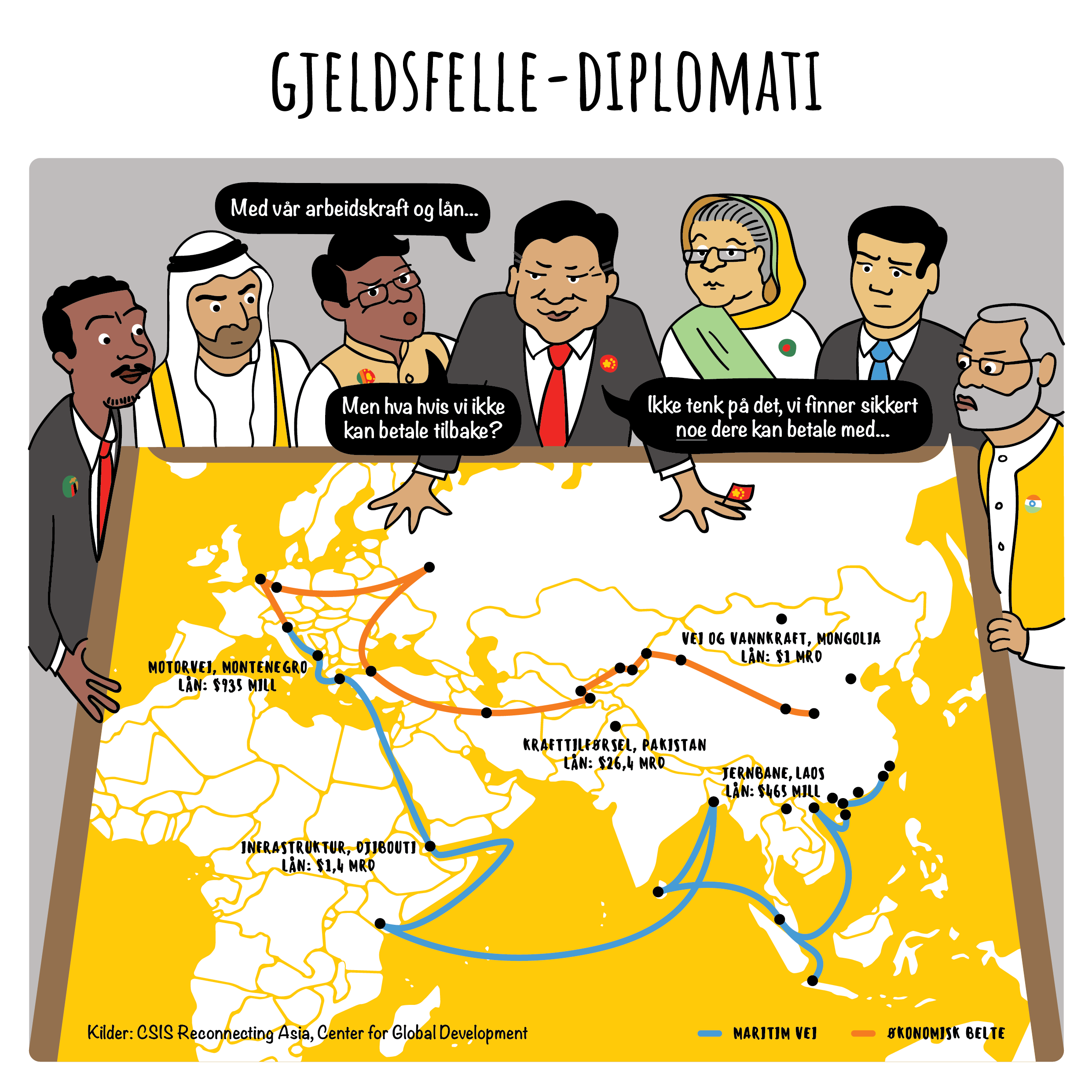

President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aligns with China’s economic imperative “Going Out” to maintain its existing growth pattern and expand this overseas. The BRI will spread China’s tentacles across Asia, Africa, Europe, and Oceania via “The Belt”, which will recreate the old Silk Road land trade, and the “Road”, which will create a sea-based trade route spanning several oceans. This ambitious initiative is expected to spur investments in large-scale gas and oil pipelines, roads, rails, and ports as well as link economic corridors.

The BRI is an evolving design. It is not limited to infrastructure; it includes “financial integration,” “cooperation in science and technology”, “cultural and academic exchanges”, and “trade cooperation mechanisms”. The BRI is also expanding geographically. In September 2018, Venezuela announced joining the New Silk Road commercial plan. Venezuela follows Uruguay, which was the first South American country to receive BRI funds.

So what are the key concerns of peoples in the Global South with regard to Chinese development aid?

Collateralizing sovereignty

Chinese loans and investments have been heavily criticized for their transparency deficit. Information on terms and conditions of Chinese loans is scarce to nonexistent and data on lending from China’s development banks are not standardized. Deficiencies in accounting could mean that the international policy community may be in the dark regarding many developing and emerging countries’ external debt situation.

As yet another debt crisis among poor and underdeveloped countries loom in the background, China’s growing ownership of key infrastructure as a result of, or built into, the terms of its loans is a cause of worry. The media is abuzz with talks of so-called China’s debt trap diplomacy. The strategy seemingly consists of China providing billions of dollars in loans to poor countries which, once they are unable to pay, are forced to give up their natural resources and strategic assets as collateral. An oft cited case is Sri Lanka’s hand over of a strategic port to China on a 99-year lease after the former could not repay its more than $8 billion loans from Chinese firms.

Business investment disguised as official aid

Chinese overseas development assistance (ODA) has often been cast as “conditionality-free” making it seemingly more attractive for developing countries. However, Chinese ODA, according to a study conducted by AidData, is intended for commercial projects and loans that are required to be repaid with interest. As observed by Matt Ferchen from the Carnegie-Tsinghua Centre for Global Policy in China, “China’s aid is only a very small part of what it considers to be development engagement, which often simply means doing business deals”.

According to Antonio Tujan, Jr., activist from the Global South, Chinese development assistance in the 1990s under Deng shifted its focus on economic and infrastructure development to promote Chinese corporate sector. Since Chinese corporations are both public and private, their overseas engagements are both investments and official aid. Thus, there is no bidding as in traditional ODA; projects are awarded to Chinese firms as investments. In BRI, 90% of projects are being built by Chinese companies. In the Philippines, 3 infrastructure projects with Chinese funding are in the pipeline: the Chico River Pump Irrigation Project, the New Centennial Water Source-Kaliwa Dam Project, and the North-South Railway Project-South Line. According to the country’s socioeconomic planning Secretary Ernesto Pernia, the Philippine government would select among 3 Chinese companies. This is a fertile ground for corruption, according the Philippine Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, since said firms can simply collude and agree among themselves on who will corner which project.

Furthermore, this arrangement is biased against domestic business and entrepreneurs. While Chinese firms and contractors will profit from their country’s “development assistance” projects, Chinese aid will reinforce dependency and potentially erode the nascent and fledgling industries of poor and underdeveloped countries.

In some instances, Chinese-financed projects are not only built by Chinese companies, but also use Chinese workers and materials. Such was the case with the construction of the Bar-Boljare motorway in Montenegro. In the Philippines, the influx of Chinese workers for the government’s mega-infrastructure program Build, Build, Build is questioned amid high unemployment rates in the country.

Fueling the climate crisis

Chinese companies have been investing heavily in coal power – especially in BRI countries. According to Global Environment Institute, China is currently involved in coal power projects in 65 BRI countries. Between 2001 and 2016, China was involved in 240 coal power projects in BRI countries, with a total generating capacity of 251 gigawatts. The top five countries were India, Indonesia, Mongolia, Vietnam and Turkey. The research also reveals that China’s involvement in coal power projects in BRI countries has been increasing overall.

If the trend continues, China will lock these countries into coal-power assets that will damage people’s health and well being and exacerbate climate change.

Suppression of rights and militarism

China’s megaprojects come at a sharp cost to human rights, causing massive displacements of communities. The China-funded New Centennial Water Source Kaliwa Dam Project in the Philippines is set to displace the Dumagat-Remontados indigenous peoples who have been living in the area and enjoying a symbiotic relationship with nature for centuries. Until now, the indigenous peoples have not been given a Free Prior and Informed Consent to the Kaliwa Dam as required by national laws. The dam will be constructed over the Infanta Fault and will be a sword hanging over the head of 100,000 people living downstream the Kaliwa River.

Such megaprojects have faced fierce resistance from affected communities. Consequently, private security companies serving Chinese companies in BRI projects have grown exponentially. In 2013, there were 4,000-registered firms, employing more than 4.3 million personnel. By 2017, there were 5,000 firms with around 5 million staff.

Chinese aid may not be significantly different from its Western counterparts after all. For China to increase its aid effectiveness it should increase grants than loans, promote partnerships that foster mutual respect, solidarity, and non-exploitation, and ensure that it does not replicate the same neocolonial relations that have tied peoples and nations to centuries of peonage and maldevelopement.

Ivan Phell Enrile is the policy officer of Asia Pacific Research Network and campaign coordinator of People Over Profit.