Debt Relief as a Response to Natural Disasters in the Caribbean

The Caribbean region combines a high degree of ecological vulnerability, including to hurricanes and earthquakes, with a persistently high external debt. The latter has domestic reasons, such as the low degree of economic diversification, but also external ones like the financial crisis with its slowdown of tourism and the abandonment of the EU banana preference policy for ACP countries. Both structural weaknesses can give reason to demands for debt relief. When they reinforce each other's negative effects, the case is even more urgent.

Disaster on a regular basis

The effects of a natural disaster on the long-term economic viability of a nation depend on two parameters: (1) its extent, measured in economic losses related to a country's GNI, and (2) its frequency. The losses of economic output are like a headwind, against which a cyclist has to ride, demanding more efforts and calories burned for a given speed and distance, without rewarding him in any way for that additional efforts - like cyclists have it, when they fight their way uphill and in exchange can enjoy an effortless high speed downhill passage thereafter.

According to calculation by Acevedo for the IMF natural disasters have on average caused damages of 5.7 per cent of GDP every year in any country in the Eastern Caribbean. Worse still, this indicator is expected to rise to 6.5% in a »no climate change« scenario and to 7.1% and 7.7% in the “mean” and “high” climate change« scenarios, respectively. However, variations in loss probability are very large, with Antigua and Barbuda (8.4 % historical / 12.9% with high climate change) in the high range, Dominica (15.0% / 23.8%) in the extreme range, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Barbados clearly below average.

What are the average periods in which hurricanes cause major damage? Regarding the OECS countries the individual probability of a hurricane striking looks a follows:

St. Lucia < 6 years

Dominica < 7 years

Antigua & Barbuda < 7 years

St. Vincent & Grenadines < 8 years

St. Kitts & Nevis <10 years

Barbados <10 years

Grenada <11 year

A debt trap with no exit

Still, the data do not describe constant outflows of resources, but occasional life-taking and extremely destructive episodes in one year, which may be followed by a longer or shorter period during which an individual island is being spared from major destruction at all.

Dominica has suffered its share of disastrous storms for statistical 15 years in 2015 with hurricane “Erica”, (destroyed an estimated 90% of GDP) and “Maria” 2017 (estimation 220% of GDP). Can it realistically expect to be spared for (at least) the next 11 years? Given that the growth reducing effects of "Erica" and "Maria" are to be felt even beyond the next eleven years, Dominica is facing an accumulation of negative growth shock effects - without any chance to escape from this specific form of debt trap.

Still the immediate quantitative problem of Caribbean debt post- or pre-hurricane is not what needs to drive any crisis resolution. It's rather the character of the debt as a trap with no exit.

This refers to a situation, where there is no more immediate link between loan-taking and investment, but the former largely serves to plug holes in the sovereign’s fiscal or external balance. Once this effect has crossed a certain threshold of indebtedness, it becomes a virtual trap. This effect is for a sovereign not different from what it constitutes for an Indian small peasant or a family business somewhere in Norway. As a general rule there is no escape from this trap other than declaring insolvency and heading for a fresh start after debt relief. This is why domestic insolvency legislation exists.

The breaking point of debt levels

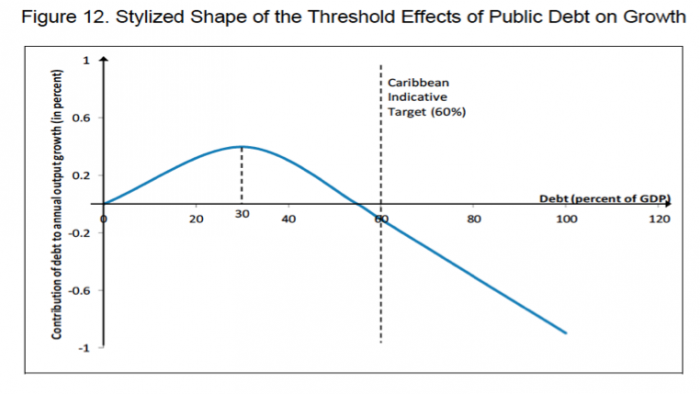

At which debt level does the trap actually snap? Based on empirical studies in the Caribbean Amo-Yatey et alia have identified a Caribbean debt threshold, past which debt merely serves to refinance existing debt service, without much of an opportunity to leave the trap without a serious debt reduction:

According to their calculations, public debt shows a decreasing marginal growth effect beyond a debt/GNI ratio of 30% and is actually causing the economy to shrink beyond 55%.

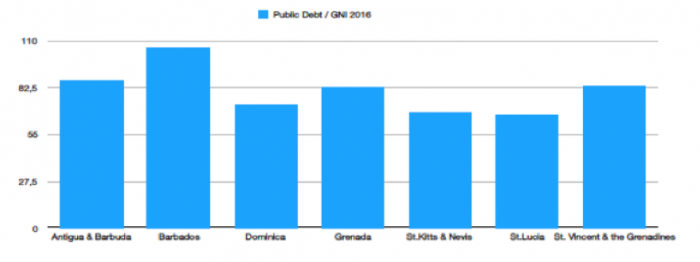

However, all OECS members as well as Barbados have a debt-to-GNI ratio clearly above the 55% threshold. This means that even absent regular new external shocks, countries would find it extremely difficult to return to a sustainable growth path.

A disaster-triggered debt relief scheme

This brings us to the necessity for Caribbean states to externalize a substantial part of the risk through an option for a catastrophe-triggered debt relief scheme.

Debt relief has the potential to provide immediate access to resources, which are already in the hands of the authorities and thus do not have to be mobilised through lengthy pledging exercises. They will normally have been earmarked for debt service in the national budgets. And they would be mobilised for emergency relief and reconstruction only in cases of obvious and undeniable need. That way the scheduled debt service would assume the role of the "fiscal buffer".

Such a scheme would imply two debt relief operations, which would respond to two dimensions of the crisis: namely

- a moratorium which would make any resource which would regularly go from the government to external creditors immediately available for emergency relief and

- a pre-designed framework for restructuring the entire stock of existing public external debt in a way which provides enough fiscal space for medium-term reconstruction under the premise that the country should not find itself in another debt distress situation when confronting the next natural disaster within the statistically averaged timeframe.

How would it work?

A stylized process beginning on day 1 after a hurricane and involving both dimensions would consist of the following sequence of steps:

- A country affected by a hurricane requests debtor protection from a pre-defined competent institution.

- An assessment based on available information leads to a preliminary moratorium if warranted in a very short timeframe.

- A period (normally 6 months) is being defined during which no debt service is being paid and no legal action against the debtor can be taken.

- A creditor committee is set-up during the 6 months period, which will start negotiations on a medium-term debt restructuring.

- Negotiations with representatives of all creditors are chaired by an impartial mediator and lead to a restructuring agreement with all creditors.

Obviously, a key element for the functioning of the scheme is the neutral and competent institution that would have the capacity to declare a moratorium and lead a restructuring process. There is more than one option as to who could actually fulfil this role:

- An existing intergovernmental institution with competence in assessing hurricane damages and/or managing debt

- A newly created body, which is created for this particular purpose.

Which are the amounts that could be made available through such a mechanism? Debt service payments by the OECS members in the fiscal years 2015 and 2016 were all in the range between US-$ 23m and 69m, which is substantial regarding both the needs as well as the absorptive capacities of post-disaster Caribbean small states.

The advantages of this solution

Beyond the quantitative aspects, there are some additional advantages of halting debt service over the mobilisation of fresh money:

- The resources are already in the country. The authorities could use them without having first to consult with anybody. They could be spent in line with the country’s own development priorities without any external interference.

- The amounts are calculable; planning for an emergency budget under the difficult circumstances of day 1 after a hurricane would be possible. The same cannot be said about officially pledged support from development partners, which in the past have sometimes been inflated by the inclusion of already pledged resources or the deviation from non-priority areas, which could damage long-term development perspectives.

- The amounts could be used without any risk-buffer deductions because they would be offset by payments otherwise made to external creditors; no contingency calculations in order to deal with potential technical or political delays in pay-outs from donors or e.g. conversion risks are necessary.

- The amounts could not be tainted with the often substantial discrepancies between pledges at donor conferences and actual disbursements which have been notorious for the international donor community, particularly when natural disasters have had a high degree of media visibility but have been put off the screens by the next disaster in a short timeframe.

Politically such a Heavily Indebted Caribbean Countries Initiative has been demanded by the recently founded Jubilee Caribbean network and is being supported by Jubilee partners in major creditor countries, including Norway.

[1] S. Acevedo (2016): Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane Climate Change Costs in the Caribbean. IMF Working Paper WP/16/199

[2]In this paper we look specifically at the Eastern Caribbean region. Unless stated otherwise data refer tot he five sovereign OECS members (Antigua & Barbuda, Dominica, St.Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Grenada) plus Barbados.

[3] S. Acevedo (2016): Gone with the Wind: Estimating Hurricane Climate Change Costs in the Caribbean. IMF Working Paper WP/16/199: 24.

[4] Moody’s Investor Service: Caribbean Sovereigns: The Silent Debt Crisis; Feb.2nd 2016, p.9.

[5] The scheme has beem modelled after the UNCTAD Roadmap and Guide for Sovereign Debt Workout; Geneva 2015

[6] As Antigua and Barbuda is not reporting to the World Bank’s debtor reporting system, annual debt service there is only estimated.

[7] Find the Jubilee Caribbean Call and its signatories at http://erlassjahr.de/wordpress...